It’s hard to find a word to describe my relationship with dystopias. I don’t enjoy them, exactly. Or like them. Mesmerized is closer—and is certainly the exact truth for some moments in some dystopias, such as A Clockwork Orange or Lord of the Flies—but neglects the element of intellectual engagement without which I wouldn’t keep reading, see above re: enjoy. I’m going to go with fascinated.

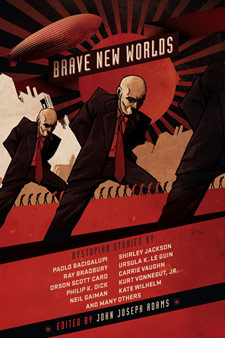

Brave New Worlds, edited by John Joseph Adams and out today, January 25th, features a mix of classics in the genre of dystopian SF (“The Lottery,” “’Repent, Harlequin,’ said the Ticktockman,” “Harrison Bergeron”) and more recent stories (the newest, “Amaryllis” by Carrie Vaughn, was originally published earlier last year), and proves pretty conclusively that I’m not the only one fascinated by dystopias.

Dystopias are mysteries. You, the reader, are trying to figure out what’s wrong with the world presented in the story when your information is almost always filtered through a protagonist who, like a fish asked to describe water, can’t recognize the oppression and cruelty he or she lives with. Most dystopias are worm’s eye views (to give three examples from this volume, J. G. Ballard’s “Billennium” (1978), M. Rickert’s “Evidence of Love in a Case of Abandonment” (2008) Kate Wilhelm’s “The Funeral” (1972)) with the occasional main character who has some power in the system (Paolo Bacigalupi’s “Pop Squad” (2006), Geoff Ryman’s “Dead Space for the Unexpected” (1994), Matt Williamson’s “Sacrament” (2009)). Views from the top are rare and tend to be satirical and depersonalized, as in “From Homogenous to Honey,” by Neil Gaiman and Bryan Talbot (1988), and “Civilization,” by Vylar Kaftan (2007) (which may, incidentally, be my favorite story in the entire collection). In general, we’re trying to figure out a dysfunctional system from within and from a perspective where information is strictly limited. And frequently, we learn more than we expected to.

I’m not going to spend this review arguing with John Joseph Adams’ definition of dystopia, although I certainly could. Instead, I’m going to say that, even if you don’t agree that all of the stories in Brave New Worlds are dystopias, you’ll find them all thought-provoking. Even the weakest are interesting thought experiments, and the best examine the darkness in the human spirit with compassion and generosity.

I’ve already mentioned Vylar Kaftan’s “Civilization,” which is wickedly funny as well as wickedly smart; it uses the form of a Choose Your Own Adventure story to point out the inevitable circularity of quote-unquote “progress,” and it won my heart forever with its deadpan side-by-side descriptions of utopia and dystopia:

Utopia […] Housing: No one is homeless. Citizens are guaranteed safe, affordable housing. […] Dystopia […] Housing: No one is homeless. People without homes live in institutions where they are subjected to conditioning and experiments.” (466-467)

I could easily spend the rest of this review raving about Shirley Jackson’s “The Lottery” (1948), but Jackson doesn’t need me to tell you how awesome she is. So I want to talk about the two other stories in Brave New Worlds that were stand-outs for me:

Geoff Ryman appears in Brave New Worlds twice, with “Dead Space for the Unexpected” and “O Happy Day!”, two quite different dystopias. “Dead Space for the Unexpected” is a satirical corporate dystopia. “O Happy Day!” is more complicated, as it takes two models and combines them to unexpected and powerful effect. The first model for “O Happy Day!” is the swathe of feminist utopias and dystopias written during the 1970s, in which men are revealed to be unsalvageable (unnecessary) brutes. The second is Nazi Germany.

In the America of “O Happy Day!” the women have taken over (ironically, by dosing the men with testosterone). Everything will now have to be utopian, except for one problem: what do you do with the unsalvageable brutes? The answer the women arrive at is immediately recognizable: you stuff them in train cars and ship them off into the wilderness to be killed. Who takes care of the bodies? Well, trustworthy, i.e. gay, men.

This is a story about so many different things, about the way that people are people underneath the labels they put on themselves and on each other, and the way that people behave badly in bad situations. And the way that even at their worst, people are capable of transcending themselves, even if just for a moment. It’s also, of course, about gender politics and ideology and using language as a political weapon. It is very, very sharply observed, and it does not let its narrator/protagonist off the hook, but shows mercilessly the ways in which he is complicit in the system of oppression he is oppressed by.

My other stand-out story, Sarah Langan’s “Independence Day” (2009), is about some of the same concerns, but for me, where “O Happy Day!” engaged mainly with history and (gender) politics, “Independence Day” poses a question about dystopias as a genre. In the Orwellian panoptical dystopia, what is it like to be the kid who turns in her parents?

Trina Narayan is thirteen, and one of the story’s strengths is that she is a believable thirteen year old; her bitter resentments against her parents are understandable, her perplexed negotiations of her propaganda-and toxin-soaked world all too plausible. When she turns her father in (for hitting her, so it’s not a simple black-is-white polar reversal, either), it’s a complicated action, selfish and bewildered and angry and influenced by factors Trina—a fish asked to describe water—can’t even recognize, much less articulate.

And then Trina has to deal with the consequences of of her actions. As with Ryman in “O Happy Day!”, Langan insists that there’s more to her protagonist than the stupid and evil thing she has done, and she shows Trina clawing her way out of the pit of banal lies and lotus-eaters, making choices that may not be good, but at least are made with awareness. It’s a tiny, partial, and probably transient victory, but in a dystopia, that’s the best you can hope for.

Sarah Monette wanted to be a writer when she grew up, and now she is.